Interesting items

Caracalla

Monetary Policy

The expenditures that Caracalla made with the large bonuses he gave to soldiers prompted him to debase the coinage soon after his ascension. At the end of Severus’ reign, and early into Caracalla’s, the Roman denarius had an approximate silver purity of around 55%, but by the end of his reign, the purity had been reduced to about 51%.

In 215 Caracalla introduced the antoninianus, a coin intended to serve as a double denarius. This new currency, however, had a silver purity of about 52% for the period between 215 and 217 and an actual size ratio of 1 antoninianusto 1.5 denarii. This in effect made the antoninianus equal to about 1.5 denarii. The reduced silver purity of the coins caused people to hoard the old coins that had higher silver content, making the inflation problem caused by the earlier devaluation of the denarii worse than it had been before.

Biography

Caracalla, also spelled Caracallus, byname of Marcus Aurelius Severus Antoninus Augustus, original name (until 196 CE) Septimius Bassianus, also called (196–198 CE) Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Caesar, (born April 4, 188 CE, Lugdunum [Lyon], Gaul—died April 8, 217, near Carrhae, Mesopotamia), Roman emperor, ruling jointly with his father, Septimius Severus, from 198 to 211 and then alone from 211 until his assassination in 217.

His principal achievements were his colossal baths in Rome and his edict of 212, giving Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the empire. Caracalla, whose reign contributed to the decay of the empire, has often been regarded as one of the most bloodthirsty tyrants in Roman history.

A rivalry between Caracalla and his younger brother Geta, was aggravated when Severus died, and Caracalla, nearing his 23rd birthday, passed from the second to the first position in the empire. All attempts by their mother to bring about a reconciliation were in vain, and Caracalla finally killed Geta, in the arms of Julia herself. Caracalla next showed considerable cruelty in ordering many of Geta’s friends and associates put to death. His expeditions against the German tribes in 212/213, when he senselessly massacred an allied German force, and against the Parthians in 216–217 are ascribed by ancient sources to his love of military glory. Just before the Parthian campaign, he is said to have perpetrated a “massacre” among the population of Alexandria.

Important for the understanding of his character and behaviour is his identification with Alexander the Great. Admiration of the great Macedonian was not unusual among Roman emperors, but, in the case of Caracalla, Alexander became an obsession that proved to be ludicrous and grotesque. He adopted clothing, weapons, behaviour, travel routes, portraits, perhaps even an alleged plan to conquer the Parthian empire, all in imitation of Alexander. He assumed the surname Magnus, the Great, organized a Macedonian phalanx and an elephant division, and had himself represented as godlike on coins.

Another important trait was Caracalla’s deeply rooted superstition; he followed magical practices and carefully observed all ritual obligations. He was tolerant of the Jewish and Christian faiths, but his favourite deity was the Egyptian god Serapis, whose son or brother he pretended to be. He adopted the Egyptian practice of identifying the ruler with god and is the only Roman emperor who is portrayed as a pharaoh in a statue.

An inconsistency characterizes the judgments about his mental state. He was said to be mad but also sharp minded and witted. His predilection for gods of health, as documented by numerous dedicatory inscriptions, may support the theory of mental illness.

Caracalla’s unpredictable behaviour is said to have prompted Macrinus, the commander of the imperial guard and his successor on the throne, to plot against him: Caracalla was assassinated at the beginning of a second campaign against the Parthians.

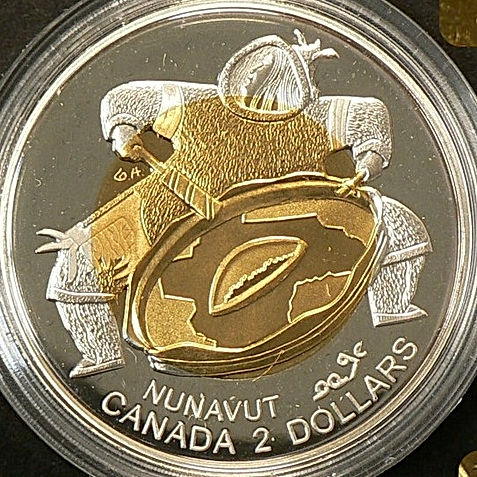

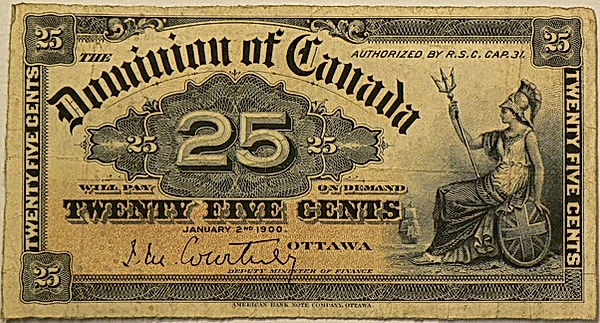

We value this coin at $100.

For more information and pieces like this one come and see us at the store!

Back to the items page